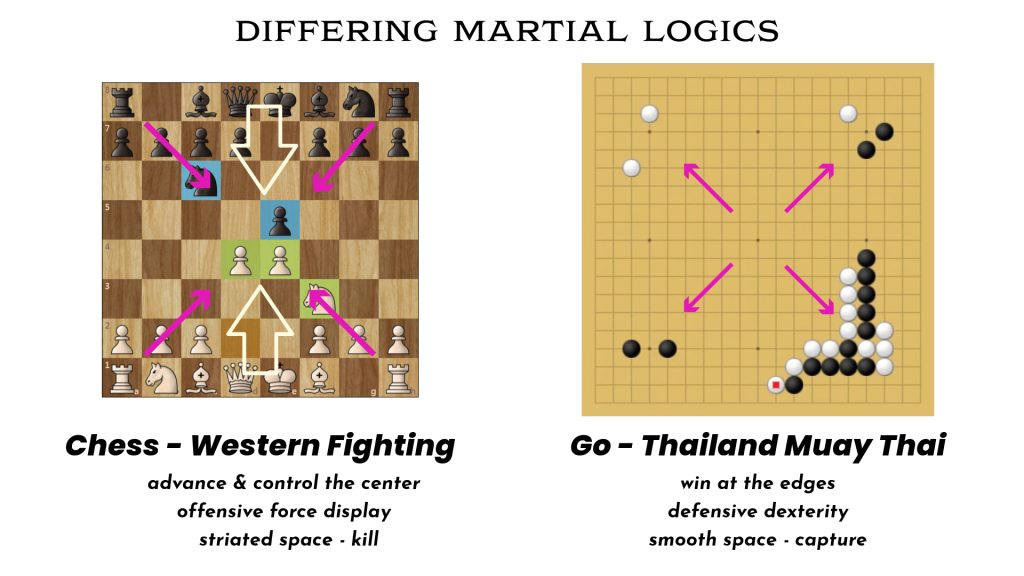

As globalizing pressures push Muay Thai toward Western-friendly viewership its worth considering the fundamental ways in which Thai and Western perceptions of conflict can differ, and the manner in which this difference is preserved and expressed as Thai, in Thailand’s traditional Muay Thai, a sport which arguably achieved its acme-form in it’s Golden Age (1980-1994). It’s the contention of this article that there are governing, different and possibly quite opposed Martial Logics that structure many Western combat sport perceptions and the art of Thailand’s Muay Thai, and that these are invoked in the graphic above showing the games of Chess and Go. Combat sports are quite diverse, even in the West, and each has its own history and audience. Each is shaped by its rules. The discussion here is more about what I’m calling the dominant image of thought as might be traced in Western and Southeast Asian regions of the world, despite rich variance, and importantly, even cross-influences.

Thailand’s Muay Thai, despite its violence, more maybe even because of it, is noted for its defensive excellence. It historically has been a close-fought sport that unlike some Western ring aesthetics, actually gravitates toward the ropes and corners, which are notoriously more difficult topographic ground. Because fighting is draw to this edge and corner emphasis, it requires even higher levels of defensive prowess to thrive at these edges. While the dominant image of Western ring fighting is much more clash-conscious, force meeting force in the middle of the ring (like two knight champions meeting at the center of a battlefield), in Thailand’s Muay Thai it is the dextrousness along the ropes, the escapability, which wins the highest esteem. This piece offers explanations for what that is so and points to other studies of Muay Thai that underpin this. Largely though, it likely relates to the way in which violence and aggression is thought of in a traditionally Buddhist society, and Thailand’s long history of a warfare of encirclement and capture.

Examples of Thailand’s Muay Thai Most Praised Edge Fighting

Thailand is not alone in esteeming edge mastery. Western Boxing has very famous rope work, some of which constitutes the highest forms of its greatest fighters. Muay Thai though has a differing dominant image of thought than in the West, even when compared to Western Boxing, one which elevates rope and corner work into its own uniquely expressive artform. Thais love the ropes. Some of this can be understood as revealing a nearly opposite generalized scoring criteria, a different conception of scoring as it relates to the fight space. In the West, being very broad about it, forward aggression is a positive signature. All things being equal the forward fighter is seen as imposing themselves on their opponent and on the fight space. In Thailand’s Muay Thai it is the opposite. This fundamental criteria reversal leads to a lot of Western viewers being confused over how Thailand’s traditional fights are scored: normally, when a Thai fighter takes the lead in a fight – something that they know in part because gambling odds in the audience have changed in their favor – they begin to retreat. The retreating, defensive fighter is seen as protecting their lead. Their defense becomes their path to victory, which is why historically Thai fighters became the foremost defensive fighters in the world. Defense takes the spotlight in almost any lead, all other things being equal. A fighter going to the ropes in the broadest Western conception is a fighter who has been forced there. A fighter who goes to the ropes in Muay Thai is, in the dominant picture of thought, signalling that they are in the lead. It’s an upside down world for the Westerner and produces a great deal of miscomprehension.

It’s best to continually return to the note that these are broad, image-of-thought pictures of aggression and ring space. Judging a fight is much more complex than this. Over the years there are pendulum swings in how aggressive or active the retreating fighter has to be in Thailand, and this is something that has differed even between the National stadia of the sport, each with their own scoring aesthetics. Broadly though, the way that the edges and corners are semiotically coded, what they signify, is as areas of control where fights are won and lost. And, because fighters in the lead retreat and defend a lot of fights head to the edges, especially in the traditional, high-scoring later rounds.

If you want to see some of the highest levels of this edge-excellence, below are select examples.

Somrak Sor Kamsing – The Eternal Braggart

I recommend this fight between two legends of the sport. Somrak in red, Boonlai in blue. Noteworthy in this fight is that Somrak at this time was one of the best Western Boxers all of Thailand. In a few years he would go onto win boxing Gold at the 1996 Olympics in Mayweather’s division. In this fight he hardly throws a punch until the fight is well in hand. The art in his arsenal is footwork, interception, movement and countering. A great deal of it, book ending the fight, happens at the edge. He returns to the edge because he is winning, and he is signalling his superiority. He has been called “The Uncrowned King” because he was promotionally denied a chance at a National Stadium belt, but he exhibits against elite competition the art within the art, indicating its nature.

Samart Payakraroon – The Jade-Faced Tiger

Another classic example can be found in this study of Samart Payakaroon, widely thought to be the GOAT of Muay Thai, facing the forward-fighting knee-fighter Namphon Nongkipahayuth (see it linked below). Watch the entire fight, but also look at the study of how Samart, almost always on the ropes, command and controls Namphon’s knee and clinch attack through interception and movement. Namphon is coming off a particularly stigmatizing loss to Samart and was in particular looking for revenge. Samart’s pliable, interceptive answer makes a particularly illuminating example of Muay Thai’s aptitude amid aggression. In a manner different than much of Western symbology, Samart is signaling his dominance through rope work, interception and evasion.

above, watch this study of Samart’s defense along the ropes in his Golden Age rematch vs Namphon2

Karuhat Sor Supawan – The Great Master

In a general way, just at the level of style, watch this highlight compilation of the switching footwork of possibly the most artful fighter of Thailand’s Golden Age, the great Karuhat Sor Supawan (below). You will see his deft switching in both attack and defense at the ropes featured here, but when in the lead and he performs his best magic, his back is to the rope. Back to the rope signals dominance. Key is understanding that as space and options shrink at the rope and in the corners, control over space becomes an even higher priority. Karuhat’s deft footwork, no matter where he is in the ring, expresses this priority, but even more-so when at ring’s edge.

Dipping into Thai History and the Games of Go and Chess

Thailand’s Muay Thai is a fighting art and combat sport of extraordinary uniqueness. Fashioned as it has been from at least 100+ years of continuous provincial fighting deep in its countryside custom – something that may stretch back multiple centuries – fortified and shaped by Royal and State warfare, itself composed of worldwide mercenary influences, from Japanese & Javanese merchant pirates to Persian & Portuguese regimented manpower, it stands as both a cosmopolitan fighting art, and still one which has been richly woven together as wholly Buddhistic Siamese and then Thai continuity. Channeled and informed by British Boxing’s colonialist, pressuring example in its modernizing period (1920-1950s), what remains most valuable in Muay Thai are the ways it is like no other fighting art. It’s a purity of difference. Both lab-tested in 100,000s of full-contact ring fights multiplied by generations, and expressive of wool-dyed Buddhistic principles, this is a synergy of provincial and the Capital fight knowledge, both martial and sport, like no other in the world. They just fight differently…and have arguably been the best ring fighters in the world.

The at-top diagram juxtaposing two combat inspired board games, Chess and the game of Go, aims to draw out some of the deeper philosophical and conceptual differences between Thailand’s Southeast Asian fighting art and many of Western conceptions of combat, especially at the dominant image of thought level.

Chess is a game of some disputed origin approximately 1,500 years ago. It was not a Western game. It’s largely believed to have come from India by way of Persia. The Western Chess vocabulary is etymologically Persian, and the Persian version of the game is closest to the one adopted in Europe. Interestingly enough, the birth of Chess and its dissemination throughout the world across tradewinds corresponds roughly to the period, 3rd-6th century AD, during which Southeast Asia underwent Indianization. Indian culture became powerfully adopted throughout mainland Southeast Asia, and importantly in the history of Siam significantly informed Khmer Empire (today’s Cambodia) royalty warfare and statecraft, much of which would be adopted by Siamese kings to the West. Royal, court and State culture was Indianized, bearing qualities (language, social forms, knowledges) which were not shared by the common populace. The Indianization of Southeast Asia has been culturally compared to the Roman Empire’s Romanization in of Europe. And to this day Thai Royalty, its Brahmin customs and practices, the common worship of Hindu gods within a Buddhist context reflects this 1,500 years of influence of Indian culture. This is to say, when comparing Thailand’s Muay Thai to the West via the game of Chess, we are speaking of a game that was of Indian and Persian origin, something quite closely braided within Siamese history. For instance, King Narai of Ayutthaya in 17th century had 200 Persian warriors as his personal guard. The influence of India and Persia is profound.

What I want you to see is that Muay Thai’s historical past is likely quite imbricated. There are layers upon layers of historical segmentation. Within this history the Royal form in particular had a distinctly Indianized history, and Thailand’s Muay Thai has had a robust Royal history surrounding the raising of armies, large scale wars at times with armies (perhaps fancifully) rumored to approach 1,000,000 men. This Statecraft heritage is likely something we can see reflected in the game of Chess itself, the game of Kings, castles and queens. And, the history that we have of Thailand’s Muay Thai is almost entirely composed of this Royal-State story, as royal record and foreign visitors to Siam’s kingdoms comprises our written history. The possible story of Muay Thai that involves provincial, rural, village, regional martial and sport practices has vanished seemingly just as much as houses of wood or bamboo will not be preserved. Yet, in the nature of Southeast Asian and Siamese fighting arts we very well may see the martial contrastive martial logic of the Siamese people, especially when compared to the visions of the West.

Chess, Go, Striated and Smooth Spaces: Deleuze and Guattari

In this we turn to the 4,000 year old Chinese and then Japanese game of Go (the game of surrounding).3 I have written about the historical origins of Thailand’s Muay Thai that particularly bring out its logic of surrounding and capture, a martial logic that is quite embodied in the game of Go (The Historical Foundations of Thailand’s Retreating Style, or How They Became the Best Defensive Fighters In the World). In short, historians of Southeast Asia point out that unlike in Europe where land was scarce (and therefore the anchor of wealth), and manpower plentiful, conquering land and killing occupying enemies formed a basic martial logic in warfare. In Southeast Asia where fecund land was everywhere, but population sparse (especially in Siam which had been one of the least populated regions of Southasia), warfare was focused on capture and enslavement. Enemy land capture was at a minimum, and even in the case of the famed and ruinous sackings of the Siamese Capital of Ayutthaya by the Burmese, the captured territory was not held. These are just very different spatial and aim-oriented logics, in fact opposite logics. I’m using the game of Go, which expresses a fluid rationality of edge control and reversible enemy capture (captured stones add to your wealth, and don’t only subtract from one’s enemy), opposed to the more centric, land-control logic of Chess. A Chess of Indian-Persian statecraft which resonated with European political and warfare realities.

This juxtaposition between games is not mine, though I’m probably the first to use it to illuminate combat sport perceptions in today’s ring fighting. It comes from the sociologically oriented philosophers Deleuze and Guattari in their book A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. A notoriously difficult work due to its heavy reliance on invented vocabularies, and its opaque, keyed-in references to specific philosophical traditions, psychoanalysis and their theoretical problems, it still provides rich analysis of buried trends in Western social organization, and a metaphysics for thinking about the history of the world as a whole.

What Deleuze and Guattari want to do in contrasting Go with Chess is to think about the different ways that Space is organized and traversed by political powers and regimes of meaning. They propose that Chess is a striated (divided, segmented, hierarchical) Space, And Go more of a smooth space. This passage from Nomad Citizenship aptly positions the Chess/Go dichotomy within a difference in how occupied spaces are constructed, which they contrast as the “polis” (city) and “nomos” (laws, customs):

“In opposition to polis, nomos refers to space outside city walls, a space not subject to the laws and mode of organization of the State (or city-State). It is in opposition to polis that the term nomos generates the sense of nomadism as a way of occupying space that is characteristic of nomadic peoples and a key component of Deleuze and Guattari’s concept. Early in the “Treatise On Nomadology,” they draw on game theory and contrast between Go and chess to explain the difference between nomadic or “smooth” space and the “striated” space of the State. Both the chess board and the Go board are composed of a square grid and thus appear striated, but in chess the battle lines are drawn by the placement of pieces in two sets of rows at the very start of the game, imposing a distinct directionality on the space of the board for most of the game (except, in some cases, for the End Game). In Go, however, pieces are placed one at the time starting on an empty board so that there is no inherent directionality involved; indeed, the entire topography of Go emerges from the ongoing placement of pieces rather than from preexisting battle lines. Chess space is also striated by the intrinsic qualities of the pieces themselves, each of which has a characteristic kind of “move” and thus controls or threatens certain rows, files or squares from its given or acquired location. Go pieces by contrast, are absolutely indistinguishable from one another and have no intrinsic qualities, their strategic value determined solely by their extrinsic position relative to the shifting constellation of other pieces on the board. Whereas the striated space of the chessboard is determined by both the initial position and the assigned capabilities of the pieces, the smooth space of the Go board starts off utterly indeterminate and only acquires a specific shape through the gradual placement of interchangeable pieces. The distribution of pieces on the Go board is like the distribution of animals on an open pasture, who occupy a space without any preassigned directions or partitions; indeed, one of the roots of nomos, nemo, means “to put out to pasture” (well before nomos became in some Greek texts synonym for “custom” and, eventually “law”). This component for the concept of nomadism thus derives ultimately from open pastureland outside city walls and particularly from a nondirectional, nonpartitioned way of occupying such space, in contrast to the space of the city, with its walls, streets, private property rights and laws”

Nomad Citizenship, Eugene W. Holland (2011)

click for DIGRESSION: The pastoral and non-City aspects of Thailand’s Muay Thai

There is in Thailand’s Muay Thai something of an ideological struggle over its nature, how much of it is rooted in Capital Warfare and Royal lineage (those social forces which write the history), and how much of it may have developed provincially and rurally in a culture of villages over the millennia (without a written history. Today traditional Muay Thai thrives in the provinces still, amid community festivals and local fight circuits, the fount of fighters which has feed Bangkok’s stadium scene, and for centuries populated the Capital armies of Kingdoms, but if you leave Bangkok even to this day and travel into the provinces you will discern more of the pastoral realm of nomos (custom) which Holland’s passage invokes. Provincial lands were marked by the movements of peoples (often by military capture and enslavement, and in modern economies by worker migration. It could be argued that the edge warfare logic of even today’s traditional Muay Thai carries the sense of smooth space traverse and custom of the land.

The much older game of Go is a strategy of surround and capture, wherein you turn an enemy’s wealth – by our analogy labor-power – into your own. This is mirrored in Siamese warfare as reported in 1688 by an Iranian vistor, “…the struggle is wholly confined to trickery and deception. They have no intention of killing each other or of inflicting any great slaughter because if a general gained a real conquest, he would be shedding his own blood so to speak” (for context, Ibrahim‘s “The Ship of Sulaiman”), full quote here. We have at surface a strong homology between foreign reports and the structural nature of the game of Go. More can be understood of my position and the role of evasion, surround-and-capture principles in this extended thread here.

Diving down into the more philosophical ramifications I provide the extended Deleuze & Guattari quotation comparing the game of Chess vs the game of Go:

“Rather, he is like a pure and immeasurable multiplicity, the pack, an irruption of the ephemeral and the power of metamorphosis. He unties the bond just as he betrays the pact. He brings a furor to bear against sovereignty, a celerity against gravity, secrecy against the public, a power (puissance) against sovereignty, a machine against the apparatus. He bears witness to another kind of justice, one of incomprehensible cruelty at times, but at others of unequaled pity as well (because he unties bonds.. .). He bears witness, above all, to other relations with women, with animals, because he sees all things in relations of becoming, rather than implementing binary distributions between “states”: a veritable becoming-animal of the warrior, a becoming-woman, which lies outside.

Let us take a limited example and compare the war machine and the State apparatus in the context of the theory of games. Let us take chess and Go, from the standpoint of the game pieces, the relations between the pieces and the space involved. Chess is a game of State, or of the court: the emperor of China played it. Chess pieces are coded; they have an internal nature and intrinsic properties from which their movements, situations, and confrontations derive. They have qualities; a knight remains a knight, a pawn a pawn, a bishop a bishop. Each is like a subject of the statement endowed with a relative power, and these relative powers combine in a subject of enunciation, that is, the chess player or the game’s form of interiority. Go pieces, in contrast, are pellets, disks, simple arithmetic units, and have only an anonymous, collective, or third-person function: Thus the relations are very different in the two cases. Within their milieu of interiority, chess pieces entertain biunivocal relations with one another, and with the adversary’s pieces: their functioning is structural. On the other hand, a Go piece has only a milieu of exteriority, or extrinsic relations with nebulas or constellations, according to which it fulfills functions of insertion or situation, such as bordering, encircling, shattering. All by itself, a Go piece can destroy an entire constellation synchronically; a chess piece cannot (or can do so diachronically only). Chess is indeed a war, but an institutionalized, regulated, coded war, with a front, a rear, battles. But what is proper to Go is war without battle lines, with neither confrontation nor retreat, without battles even: pure strategy, whereas chess is a semiology. Finally, the space is not at all the same: in chess, it is a question of arranging a closed space for oneself, thus of going from one point to another, of occupying the maximum number of squares with the minimum number of pieces. In Go, it is a question of arraying oneself in an open space, of holding space, of maintaining the possibility of springing up at any point: the movement is not from one point to another, but becomes perpetual, without aim or destination, with out departure or arrival. The “smooth” space of Go, as against the “striated” space of chess. The nomos of Go against the State of chess, nomos against polis. The difference is that chess codes and decodes space, whereas Go proceeds altogether differently, territorializing or deterritorializing it (make the outside a territory in space; consolidate that territory by the construction of a second, adjacent territory; deterritorialize the enemy by shattering his territory from within; deterritorialize oneself by renouncing, by going elsewhere . ..). Another justice, another movement, another space-time.“

Deleuze & Guattari, “1227: TREATISE ON NOMADOLOGY—THE WAR MACHINE“, A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism & Schizophrenia

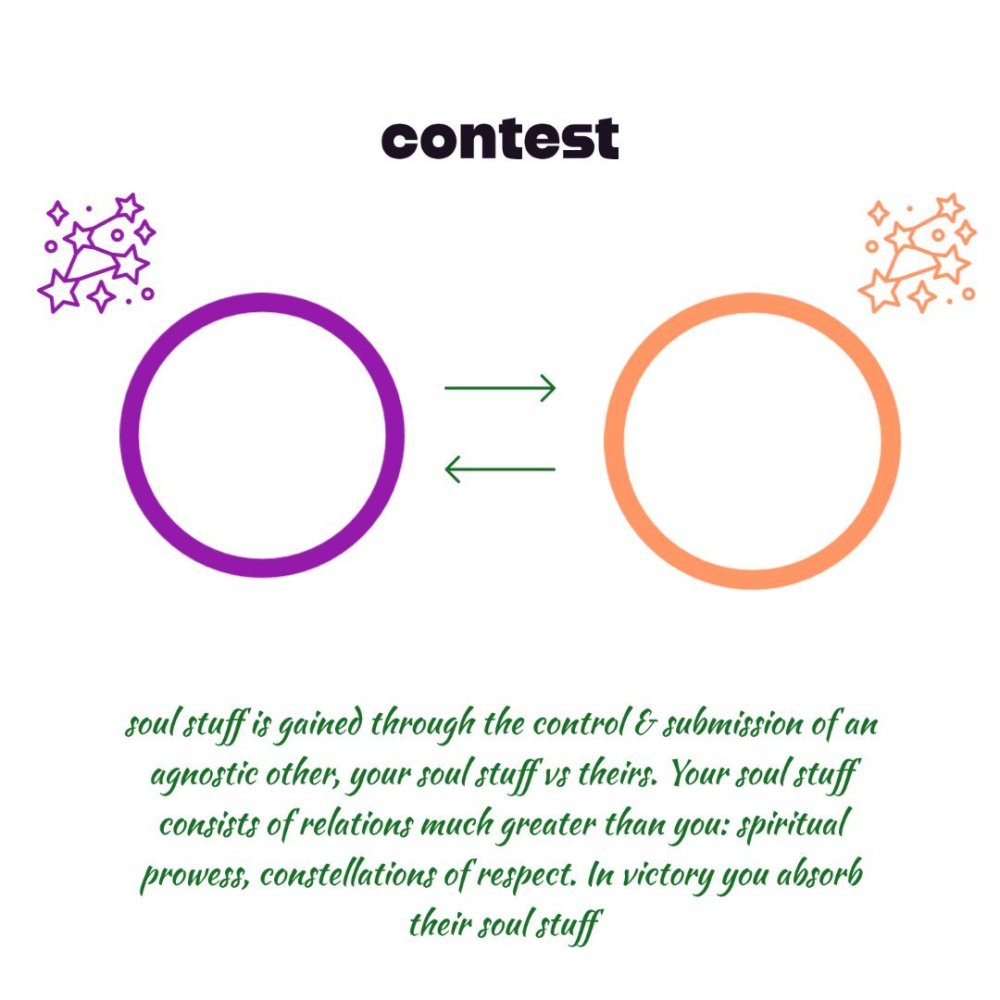

Becoming and A Warfare of Capture

What Deleuze and Guattari are invoking is a conception of warfare which is much more fully potentiated. Not locked into rigid hierarchies and roles of figures of power, it is a much more metaphysical battle that reflects aspects of what I have argued is the spiritual foundation of Thailand’s Muay Thai, an animism of powers within the history of the culture that predates the arrival of Buddhism (Toward a Theory of the Spirituality of Thailand’s Muay Thai). This logic of an animism of powers contains an essential aspect of captured power, the incorporated power of a captured enemy, founded on what historians of Southeast Asia have called “Soul Stuff”, roughly equivalent of Hindu shakti (strength). This can be manifested in captured slave labor, or perhaps even in the prehistoric rites of cannibalism through which one consumed the soul stuff of an enemy. You can find a logic of Soul Stuff here, this graphic below helps represent the animism of contest. A primary source on soul stuff and a fusion of military and spiritual prowess can be found with historian O.W. Walters here. Thus, within the cultural origins of Siamese culture, even that which pre-dates the Indianization of the region, we have essential aspects of a smooth, tactical space in a Deleuze & Guattari sense, which potentially maps quite well into the game of Go, especially as it is contrasted to Chess.

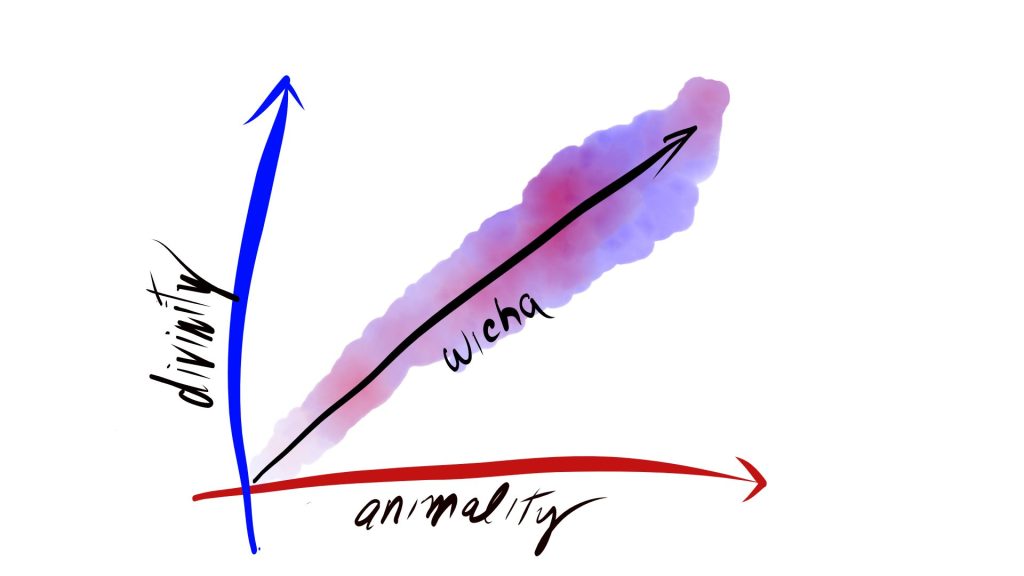

Further in concordance with Deleuze & Guattari’s philosophical concept of liberty is the way in which Thailand’s Muay Thai can be understood as revolutionary in their terms. Deleuze & Guattari write of becoming-animal, becoming-child, becoming-woman, deterritorializing flights inimitable to human freedom. Thailand’s Muay Thai (& broader Thai agonism) de-privileges these categories, along a continuous spectrum of thymotic struggle, which runs thru the social hierarchies of low to high, sewing them together. One could say a smooth thymotic space of trajectories. Thailand known for its (ethically criticized) child fighting, women have fought for 100+ yrs, and beetle fighting embodies much of the Muay Thai gambled form. In many important ways Thailand’s Muay Thai avoids the stacked arboreal structure of Western Man (& its contrastive Others), favoring a continuity agonistic spectrum within its (Indianized) hierarchies. It has strongly weighted traditional hierarchies, but within this a thymotic line-of-becoming that runs between divinity and animality. see Beetle Fighting, Muay Thai and the Health of the Culture of Thailand – The Ecology of Fighting

more on the division of divinity and animality by wicha here: Muay Thai Seen as a Rite: Sacrifice, Combat Sports, Loser as Sacred Victim

Knowing-as-doing, the wicha of technical knowledge of how to do, runs between the axes of divinity and animality in a way that supports a mutuality of any figure’s becoming, from the insect up to the heightened champion fighter, in a line of flight shared by others. Most Deleuzian becoming-animal, -child, -woman examples come from the arts (sometimes the bedroom), but instead in Thai, gambled agonism we have the becoming of actual animals, children, women & the projective affects of an equally agonistic audience undergoing its own becoming-as. When I say revolutionary, I say “Thailand’s Muay Thai has something to teach the world about the nature of violence and its meaning.”

Learning From Chess in How to See Thailand’s Muay Thai

Keep in mind, this isn’t an direct one-for-one comparison of the contemporary game of Chess (and Chess Theory) and the ring sport of Muay Thai. It compares the dominant image of thought in the conceptual trend. Some have pointed out that my gross picture of Chess leaves out its post-1920s modern Chess Theory development, which often eschews central forward advancement. What is important in the Chess example isn’t how Chess was played in 1960s, say, but rather that Chess over the sweep of its history allows us to see how it expressed the martial logic from which it came, ie, how some battles were fought in the field, with advancing lines, and a central capture of territory focus. Chess I would argue contains a martial logic fingerprint in its organizational structure, just as the real life political powers of Kings, Queens, knights and bishops made their impact on its rules & formation, the increased power of the Queen on the board said to be a fine example of this (see: A Queen in Any Other Language). Even in the Hypermodernism of Chess one might say that the center still holds importance, as there are just other ways of controlling or managing it. Hypermodernism for instance may have reflected the increased use of cannon & then WW1 artillery. Between the two games of Chess and Go are differing Martial Logics. It doesn’t mean that there is zero fighting for the center in Muay Thai (or in Southeast Asian warfare…siege warfare is prominent in Ayutthaya history for instance, though with influence from the Portuguese, etc), or that there is zero edge or flank control in Western European warfare or Chess (flank maneuvers are numerous in European warfare). The contrast is really meant to exposed how we perceive conflict spatially, and that these are things we’ve culturally inherited. You see these inherited concepts, for instance the centrality of territory capture in common Western scoring criteria like “ring control”. Centralized conflict is part of our past and informs how we judge fighting styles, just as edge conflict is part of Southeast Asia’s past. And importantly this also informs our ideas of violence, with a European tendency toward “kill” (to control land, ie the center) and a SEA tendency toward “capture”(to control labor, ie the edge).

FOOTNOTES

- Somrak (Pimaranlek Sitaran) vs Boonlai Sor.Thanikul, June 11, 1991 ↩︎

- Samart Payakaroon vs Namphon Nongkeepahayuth – December 2nd, 1988. A rematch of Samart’s November 28th victory ↩︎

- wikipedia: Japanese word igo (囲碁; いご), which derives from earlier wigo (ゐご), in turn from Middle Chinese ɦʉi gi (圍棋, Mandarin: wéiqí, lit. ’encirclement board game’ or ‘board game of surrounding’) ↩︎

subscribe to new Philosophy of Muay Thai articles, support this writing

subscribe to new Philosophy of Muay Thai articles, support this writing